I experienced a strange confluence of public, historical and personal events last week:

-

I was asked to lecture at student film project about How and Why the Holocaust Happened.

-

International newspapers revealed that some “inalienable rights” – expectations of privacy — for the American citizenry are in fact alienable on a federal scale.

-

A few students graduating from Laguna Blanca School told me their thoughts on “Big Brother” snooping in their communications and research.

Bear with me: these things are totally related.

Beginning with Monday’s news: the Supreme Court rules 5-4 that taking DNA evidence of all arrestees nationwide, using the personal information in a national crime tracking data-base for unsolved earlier crimes, does not constitute an unreasonable search and seizure.

Justice Kennedy writes the explanatory majority opinion: a mouth-swab taken from a suspect is not an intrusive means of identification. “The only difference between DNA analysis and the accepted use of fingerprints databases is the unparalleled accuracy DNA provides.” Indeed, we have ever-evolving tools for the criminal-detecting job. It’s hard to argue with greater efficiencies there: how infuriating are recidivist criminals who aren’t convicted for their violence the first time, and escape justice again because preponderance of the evidence is lacking?

Trouble is with the definition of “criminal.” That term is now broad enough to include you and me arrested for – oh, let’s say, a silent protest outside of Vandenberg Air Force base or an educational field trip to Cuba. As Justice Scalia – bizarrely aligned in this case with the women justices on the court, Ginsburg, Kagan and Sotomayor—wrote in a scathing dissent: “Make no mistake about it: Because of today’s decision, your DNA can be taken and entered into a national database if you are ever arrested, rightly or wrongly, and for whatever reason.”

By Friday, we had the disclosure of another privacy erosion to digest: the Washington Post and Guardianreport – and U.S. Executive and Legislative lawmakers readily defend — the 7 year existence of the biggest secret surveillance programs monitoring the internet activity and phone communications of innocent people in human history.

The internet monitoring program is called PRISM and has the apparent cooperation of Google, Yahoo, YouTube, Microsoft, Paltalk, AOL, Skype and Apple. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberginsists that they are not willingly allowing the government to “tap directly” into their servers. Whether or not the government is doing so using a contracted third-party remains an area of speculation.

The communications program involves Verizon, AT&T and other telecom giants: they are collecting something called “metadata,”– a qualifying term that many of us with and without law degrees just learned. Program advocates claim this is acceptable information capture because the government is merely aware of when and to whom you make a phone call, not the contents of that phone call – unless you give them a reason to listen in. Obviously, they’d find a way to make listening legal if they wanted to, but hey – isn’t that what we want law enforcement to be doing? Catching the “bad guys” before they do something bad?

The Obama administration was quick to defend itself and the secret programs as “limited” with “procedural safeguards” to prevent overreach. Director of National Intelligence James Clapper bullet-pointed out the many ways in which the government wolf is keeping watch over its own hen-house. His defensive outrage assumes a predictable “kill the messenger” whining: of the phone-tracking program, Clapper says its “reprehensible” for the Edward Snowden and journalists to have informed the public of these important programs in the first place: “The unauthorized disclosure of a top secret U.S. court document threatens potentially long-lasting and irreversible harm to our ability to identify and respond to the many threats facing our nation.”

So big wow: it’s finally out. The government is capturing our DNA, monitoring our internet searches and phone calls!

To quote a graduating teenager: “Well, duh.”

None of this is surprising to those of us who were scandalized by the intrusive powers the government conferred upon itself with the Bush regime passage of the Patriot Act six weeks after 9/11, again in 2006 and again by the Obama administration in 2011. The sweeping consolidation of Executive power through expansive roles in the Treasury Department, law enforcement and other mechanisms designed to “remove obstacles to investigating terrorism.”

The President is unapologetic: “It’s important to recognize that you can’t have 100% security and also then have 100% privacy and zero inconvenience.”

We have to make choices as a society.”

The trouble with this is that we weren’t asked to make any choice about being “metadata-ed”, it was made for us. Now we’re being told, ex post facto, that this information-collection-privacy-intrusion mechanism exists. And we’re expected to trust that it won’t be abused.

Fascinatingly, the students I spoke with are not worried about Executive Power over-reach:

“If I’m not doing anything wrong, why should I care if the government is reading my emails or texts?”

“They are more likely to catch terrorists if they have the right to track everyone.”

“Obviously they are spying on us. (shrug) But whatevs.”

The students’ reactions mirror those of the general public. As David Lazarus’ reports in “The surprise about spying on Verizon clients: little outrage” in the Business section of the LAT 6/7/13 ”We’ve gotten so used to having our privacy violated, we’re just not shocked any more to learn that someone is peeking over our shoulder, whether that’s a hacker, a marketer or the NSA.”

I hesitate now to bring up the Holocaust, but I will anyway.

A caveat: I’m personally disinclined towards alarmists’ projections that apparent insanities of federal policy are indicators of our descent towards an Orwellian dystopia. We’ve got some incredible minds at the ACLU working overtime, and they aren’t known for losing epic wars of attrition.

However, when it comes to fights between individuals and governments over civil rights, transfers of power from the public to the executive branch and the effort to later reclaim this ground, we look to history for guidance. Is there a precedent for rolling back civil liberties under the banner of national security? What were the outcomes of those incidences? At what point did the citizenry realize what was happening to their Republic and were they able to restore the personal rights they had been deprived of in the fear frenzy?

It’s obviously not reasonable to equate the U.S. government’s behavior since 9/11 and the groundwork Hitler meticulously laid for “The Final Solution” as analogous developments. Among the many notable differences is the declaration of war against a common noun (“Terrorism”) rather than a proper noun (“Jews”).

Regardless, it’s important to observe that the summary dispensation of due process and concentration of expansive powers in the Executive (ie; Chancellor, Czar, President, King, etc.) sets a permissible legal framework for all subsequent actions under the aegis of “national security.”

To put the point more directly: The Holocaust was legal.

Two months after a terrorist attack against the Reichstag building in 1933, German Parliament passed the Enabling Act (“Law for removing the distress of people of Reich”) which transferred power from Parliament to the Chancellor for a period of four years. It expressly permitted the Reich cabinet to act in ways which “might deviate from the Constitution.” To placate those concerned about the transfer of power to a dictatorship, Adolph Hitler promised that his government would “make use of these powers only insofar as they are essential for carrying out vitally necessary measures.”(See the The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany by William Shirer)

So began a reign of terror against a designated people.

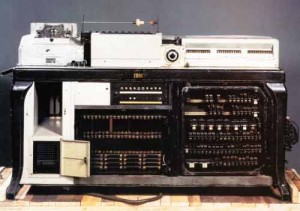

In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws forbade civil interactions (including marriage) between these people and others. Subsequent laws followed banning the targeted citizenry from public spaces, government jobs, medical care and property ownership. In 1938, during Kristallnacht, the very identity of these people was deemed criminal and the government sanctioned widespread violence against their homes, synagogues and bodies. They were deported to ghettos, concentration camps and prisons. By 1939, it was a matter of policy for these “resident criminals” to self-identify in public with a yellow Star of David on their exterior for ease of identification. The Executive government kept meticulous records of the targeted population, using the best computer-technology available — the IBM-created Hollerith machine — for efficient tracking. Hollerith-generated verification numbers were made permanent as tattoos on human flesh.

We know how this story ends: 11 million people exterminated in an unprecedented campaign of industrial genocide.

When Holocaust survivors speak about the horror they tell of how gradually it all began. How Germany had been reeling from war and terror attacks. How the resurgence of nationalism and mass media propaganda endorsing consolidation of power in the Executive branch was deemed necessary for national security. How people were originally unified around the feel-good nationalism of their eloquent leader. How they were initially more afraid of terrorism and internal chaos than they were of their own government. And, when the abuse of power began to make its dark forces known, how people quietly acquiesced or attempted to evade notice of resistance in order to keep themselves and immediate families safe.

Many reasonable German citizens didn’t resist immediately for a variety of reasons – There had been episodic crack-downs on people in the past, and it never achieved such horrific proportions. Compromises to liberty and freedom seemed necessary for order and security. And, the “not-my-problem” reasoning — some of which I’m hearing repeated in today’s teenagers.

My simplistic conclusion is that there are predictable patterns we should be teaching students to observe on a global and historical scale: When a government over-reaches its authority, and the public passively surrenders its critical voice, it’s usually because of (1) A dramatized terror threat (2) Apparent trust in officialdom and (3) Distracted self-interest.

The flimsy inoculation against the call to give-a-sh*t about the danger this represents is usually: “It’s not affecting me.” The vaccine of arrogance has an expiration date, of course.

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out–Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out–Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out–Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me–and there was no one left to speak for me.

Regarding war and national security in a democracy, the tension between collective security and personal freedom is dynamic and contextual. It requires vigilance. An aware and literate population can keep the cautionary tales of history, the promise of the Bill of Rights, and the gradual encroachment of febrile military policies in a reasonable balance.

What’s changed since 9/11 is the conceptual definition of guaranteed rights and freedoms: our students aren’t outraged about a loss of privacy they never grew up expecting was theirs with in the first place. This year’s high school graduates were in Kindergarten when the Patriot Act was passed in 2001.

As Justice Thurgood Marshall reminds us:

History teaches that grave threats to liberty often come in times of urgency,when constitutional rights seem too extravagant to endure. The World War II

Relocation-camp cases, and the Red Scare and McCarthy-era internal subversion cases, are only the most extreme reminders that when we allow fundamental freedoms to be sacrificed in the name of real or perceived exigency, we invariably come to regret it

Justice Thurgood Marshall’s dissenting opinion in

Skinner v.Railway Labor Executives Association (1989)

By Alethea Paradis