“War is what happens when language fails,” observes Margaret Atwood. In this sense, the crude methods of uncommunicative adversaries are not unlike pre-verbal toddlers resolving territorial and property disputes with violence. But on closer inspection, these words reveal a broader truth about cultural literacy and peace: what if war is the goal of an Elite, and manipulating the masses to sanction unjustified conquest is a function of carefully tailored words? In this case, it isn’t the language that fails, but the listeners.

When our students aren’t listening, is it because we never earned their full attention?

Our job as educators is to inspire critical thought, impart the tools for creative problem-solving and innovative solutions. It’s important for students to acquire experiential confidence with the logic of war-language, lest they be awed by the powerful, masquerading as visionary.

“Just War” theorists—ranging from ancients (Cicero, St. Thomas Aquinas) to the industrial (John Stuart Mill) to the modern (Ron Paul) — have long opined upon the concept of Bellum iustum: under what limited circumstances war is the moral choice. Widespread literacy of these principles might inhibit a sustained campaign of manufacturing public endorsement for the Pentagon’s violence. But let’s be honest – applying such sensible abstractions in reasoned dialogue against a multi-media, billion-dollar-barrage of war fever is difficult, if not altogether impossible.

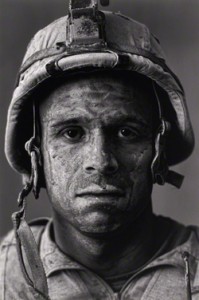

It’s easy to understand why a democratic citizenry largely untouched by war surrenders critical thought to emotional appeals of “liberation,” “freedom” and “heroism” as justification for violent action. From what experiential reference – other than the visceral entertainment of war movies – might American civilians understand the true misery of war? Without directly experiencing combat, administering trauma care to civilian refugees, collecting testimonies of war orphans, inhaling the stench of a torched landscape, burying the dead – war might seem like the most expedient way for a powerful and *noble* nation to have its goals accomplished.

“

What if schools throughout the United States committed to foreign exchange programs for students to visit countries healing from war – experientially, building muscle memory and critical thought of its avoidable horrors — in a posture of safety, compassionate adventure and intelligent foreign policy study?” Imagine it. Today’s high school students were no more than pre-school children when U.S forces invaded Iraq. Who but historians could have predicted the ensuing catastrophes? “Fallujah and Abu Ghraib; thousands of American lives lost and damaged; at least 125,000 Iraqis killed, and some 3 million others exiled or displaced; more than a trillion dollars squandered.” (Harper’s Magazine / March 2013) The ten-year anniversary of the war came and went this spring with little fanfare. Hardly a victory can be claimed for a war so contrived: with no evidence connecting events to Al Qaeda, the Bush administration masterfully captured our collective grief from 9/11, marched us to the gas pumps to “yellow-ribbon-up” our SUVs, and wave the flag of righteous indignation over a mission to “liberate” a historically volatile region from non-existent Weapons of Mass Destruction.

In what would become one of countless Orwellian constructs of linguistic reasoning, then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld accounted for the lack of WMDs in Iraq with this gem: “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence!”

(Most of our students can refute that one with both hands tied behind their cell phones.)

Boston University Professor and Vietnam War veteran Andrew J. Bacevich, pens a thoughtful letter to one of the Iraq War’s chief architects. In

A Letter to Paul Wolfowitz, Bacevich dissects the Bush Doctrine of “pre-emptive” war, while posing some brilliant questions about the lie the American public allowed itself to believe of the Iraq War:

“One of the questions emerging from the Iraq debacle must be this one: Why did liberation at gunpoint yield results that differed so radically from what the war’s advocates had expected? Or, to sharpen the point, How did preventative war undertaken by ostensibly the strongest military in history produce a cataclysm?”

One of the benefits– if I may be so bold – of the Vietnam War, is that its lessons can still be discovered, learned and applied to the modern day. Dynamic teachers do this:

Educational travel programs to Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam – like those provided by the educators at

Peace Works Travel – connect students to real people still living with the legacy of war.

Our student travelers from

Harvard-Westlake school spent their spring break interviewing amputees along the Ho Chi Minh trail. Students returned to the U.S. energized and engaged: they formed a SayNoUXO club and are publicizing the plight of Unexploded Ordnance victims in Laos through video and awareness campaigns. Exceptional student thinkers from

Francis Parker School are exploring the history and consequences of war with annual spring break trips through Vietnam.

Watkinson School embraces experiential study of surviving the Khmer Rouge genocide with music via educational field trips through Cambodia. On every educational journey, our students engage with our NGO partners serving people transcending war. Students return from our program enlightened, inspired and committed to exploring mutually-beneficial international alternatives to war. These travelers are forever impacted; they now consider unanticipated consequences to violence. They now believe, as one student remarked, “whatever the question, war is not the answer.”

Many of our war survivor-friends did not exist when these conflicts began. As then-Secretary of Defense Robert S. MacNamara absurdly championed military escalation in 1965—and Vice President Dick Cheney speciously repeated 35 years later — U.S. forces of aggression would be greeted “as liberators,” victims of this cavalier violence in the destination countries were yet to be born. Today, survivors’ poignant stories of hardship, indiscriminate suffering and loss are tempered by the equally profound lessons of hope: humanity can avoid, transcend, and heal from war. Students emerge from these educational field trips profoundly motivated to engage in our democracy, to perceive –and then reject–their leaders’ pseudo-intellectual appeals to war and to innovate mutually profitable relationships with global partners working for stability.

Ultimately, Bacevich implores Wolfowitz to do with Iraq as the putative “best and the brightest” civilian mind behind the Vietnam War — Robert S. MacNamara – did with SE Asia: admit that he’d been “wrong, terribly wrong” about the U.S role in Indochina.

Perhaps our nation will not hold its breath for

ex post facto apologies if our citizenry can detect and resist war fever as it is occurring. I’m confident that a broad movement of global educators committed to

educational travel abroad for students can have an impact towards deterring the next war that the profiteers have already inked on the calendar.