Monday, April 9, 2012

Living Legacies: the Human Cost of the "Secret War"

A special guest blog by PWT’s founder, Alethea Tyner Paradis, reflects on the lingering effects of the CIA’s “Secret War” in Laos, while traveling with a group of students through Xien Khuang and the Plain of Jars.

We travel the bomb-riddled mountains riding aloft in our air-conditioned private bus, views of a struggling existence rolling along like scenery recycled indefinitely. I watch our students capturing mental snapshots of this other-worldly poverty. Hallow-eyed Laotian children hauling water along pothole-punctuated roads, slash and burn agriculture torching the landscape and skies, elderly women bent with gravity of firewood bushels, thatched roof villages perched precariously over unstable cliffs, all one major rainstorm away from catastrophe.

As we approach a humble preschool, clutching cameras and quiet apprehensions, the people welcome us with genuine grace, hands-at-heart, bowing a prayer-like greeting “Sabaidii!” “Hello!” Their tiny pupils are mesmerized by our group of fair-skinned pilgrims offering gifts of clothing, art supplies, balloons and nursery rhymes. The pure sweetness of their curious spirits enchants us all. Would a roomful of forty American five-year olds sit as patiently for these tedious introductions and tri-lingual translations? Hmong. Lao. English. Mutually unintelligible tongues require the universal language of play. Laughter, it turns out, sounds the same to every age and ear. Older students crowd in through windows and doors, hoping to glimpse the novelty, joy by proxy.

It’s unthinkable that these beautiful, simple lives are lived in fear of subterranean munitions.

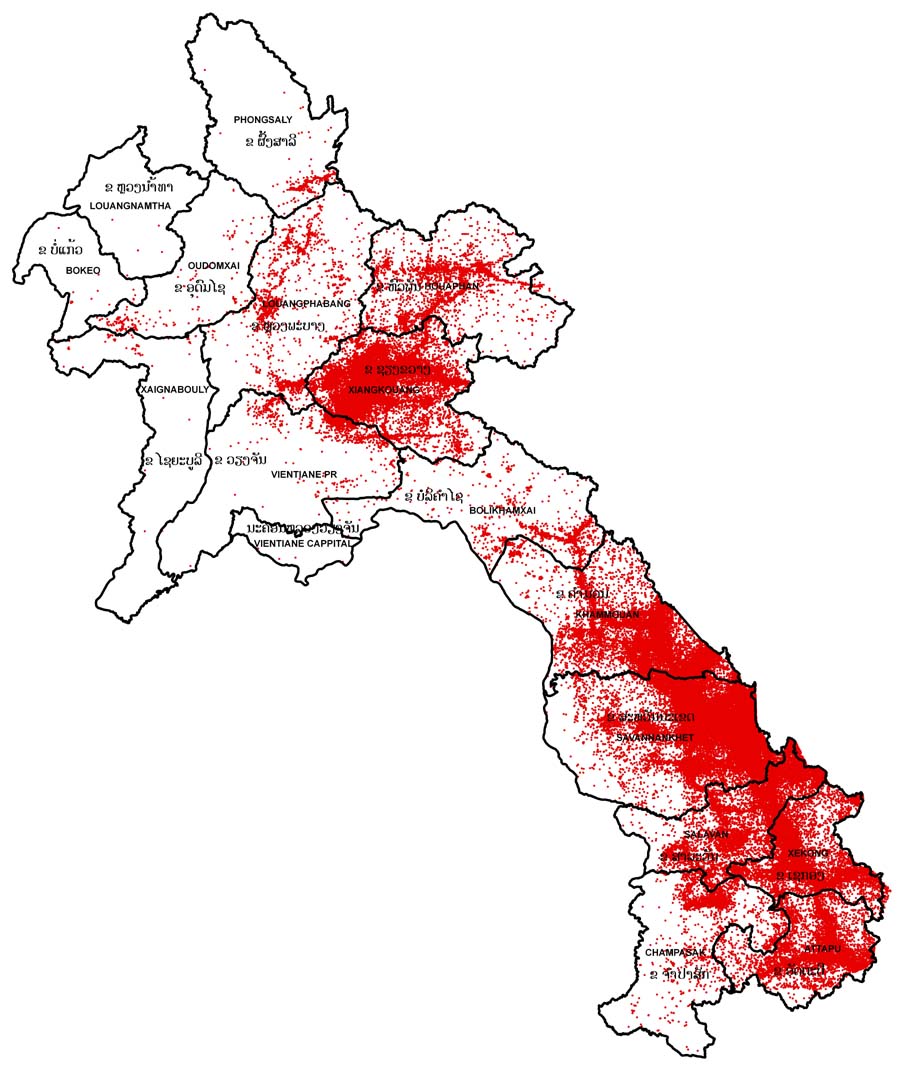

The Xien Khuang villagers, and thousands like them along the Laos -Vietnam border, subsist in history’s shadow, deadly threat of UXO littering their landscape. The last of their victims, mere “Collateral Damage” from the United States’ “Secret War” and 9-year bombing campaign remain, as yet, unborn.

Here, the moral calculus of a deliberate versus an unintended target is meaningless. Body counts matter no more. Cold War Games whose players have long abandoned the field, left a deadly scorecard for generations of innocent spectators.

We walk through the adjacent village where these lovely preschoolers call home, parading ahead and behind us with giddy chatter. Pigs, cows, chickens, ducks, dogs and water buffalo share terra firma with humans. Tidily swept hard-packed dirt spaces offset by bamboo stick fences demark one family mud hut from the next. The average family has over 5 children. Giant, rusty satellite dishes occupy every yard. Old steel US bomb casings are repurposed for their utilitarian value: water troughs, planter boxes, porch supports and walls. Everywhere: bare bottom children are dashing about, chasing animals. Roosters squawk in competition. Women are working: weaving, washing, wearing babies. Men are using heavy tools, engaged with the industry of wood, resource processing, imparting machete tutelage to young boys. Other men are slouching around small tables, glassy-eyed with conversation and bottles of Beer Lao, oblivious to indignant women with backs turned in disapproval. We stride with purpose through this uncomplicated place to meet two mothers whose lives are simple no more: they lost their 5-year-old children to UXO in 2008.

We are all a little nervous. This feels too personal, and yet like the allure of a highway traffic accident, we cannot bring ourselves to avert our gaze. The women speak quietly in turn, eyes downcast. They were in the rice fields working that day. The kids were playing in groups, ostensibly supervised by their elder peers. They found a “Bombie.” Ignorant of its danger, they tried to crack it open. The blast killed our children and injured two others.

While exceedingly polite and compassionate, our students’ reactions to the first hand testimonies we offer on this edu-charity adventure have been cautious, muted, understated. As teachers, we couldn’t risk an awkward silence this time.

“Think about what you want to ask someone in their situation.”

The students brainstorm brilliantly:

“How do you feel about Americans?”

“How have you found the strength to go on with your lives?”

“What do you want us to tell people back at home about the problems here?”

“How can we help?”

Though we had rehearsed questions to follow the recounting of the tragic stories, we had not anticipated the editorial license of our interpreters. A one-line response from the grieving mothers yields a long-winded translation, the content of which does not match the facial expression of the speaker. It is evident that our visit, though well-intentioned and purposeful in the long term, requires a painful reflection on the permanency of loss—the persistent fear and danger in their futures. When it is revealed that we have donated money to put their surviving children through school in preparation for college, there is no joy recognizable on their faces. How could this generous gift remotely approach an easing of their pain? Our guide listens to her short response and translates into English: “Thank You. We are very happy you came to visit and speak with us today.”

It is estimated that 30% of Laos remains contaminated with UXO. At the current rate of bomb removal, it will take over 2500 years to restore the land to safety. (source: COPE, Vientiane) Politicians are quick to remind us that the US is taking responsibility and appropriating funds for cleaning up its cavalier cruelty. After all, we spend more annually than any other country on UXO removal in Laos: in 2011, 9 million dollars. Sounds like a lot? We spend more before breakfast every day occupying Afghanistan and Iraq.

Decommissioning UXOs is expensive, tedious, dangerous work. Mines Advisory Group, (MAG), a British NGO does so admirably around the world. In 2005 they cleared the Laotian equivalent to Stonehenge, a mysterious UNESCO World Heritage site known as The Plain of Jars. As we walk through, speculating on the meaning of these Iron Age vessels that survived the air raids, the natural losses are evident. Denuded forests. Bomb craters. “DANGER!” signs caution us from venturing a field.

One of our students inquires about the narrow ribbons of land threaded between the MAG safety zone markers: “Why did they only make pathways this wide rather than clearing the whole place?” Clearly there exists the technology, the expertise, the desire to vacate more land. His question strikes me as precious: Of course we should make every footstep free of deadly ambush! Inexplicably, I feel like crying. “It’s expensive,” I say, knowing the price tag: $1,000 US dollars will clear 5,000 square feet of flat ground. In a developing country where people live on $1.50 per day, UXO removal literally costs a fortune. Simple instincts of value and logical action seem obvious to a young mind: He says: “Yeah, but so what? It’s worth it.”

Our group later patronizes the MAG visitors’ center on the dusty main street of Phonsavan. Students are treated to a personal revelation by the lone employee, who shows them his chest and stomach scars from a “Bombie” detonation he suffered as a pineapple farmer, hoeing the soil. Though externally perforated with shrapnel, his internal organs survived. Our group is speechless. Searching for a hopeful remark to fill the silence, I say: “Wow. You are lucky to be alive.” Understanding perfectly, he shrugs, “Perhaps.”

Laos Student Trips,Political Thoughts,Student Community Service