Investigative Journalism - Xieng Khuang to Luang Prabang and Home Again

|

|

“Thongchanh discusses monastic life with a young novice.”

|

We ride aloft in air-conditioned comfort, our safe passage facilitated on a ribbon of concrete threading through bomb-riddled mountains. Scenes of endemic poverty roll by the tinted bus windows like history repeating itself. Thatched-roof dwellings frame the margins of the road, bamboo-woven walls, mud-packed floors. Barefoot children chase chickens, women bathe unselfconsciously outside, old people haul bushels of natural resources harvested from Earth spared the ubiquitious slash and burn. Vibrant growth of tropical green banana trees, over-grown vines, terraced vegetable gardens and flowering plants contrast against a smoky sky. Scorched acres reach into the horizon and tumble to the valley below. Life is precarious here. Vulnerable shelters housing three-generation families are one violent storm shy of catastrophe. It is here that an average of one farmer— or child—per day will unintentionally detonate subterranean munitions dropped from the U.S.-dominated skies in a war few remember and none asked to fight.

The students are tired. Immersed in the escape of iPods and attendant ear-buds, they loll listlessly as our

|

| Cluster Bomb in it’s original casing |

oversized vessel rounds the tight corners of this 7 hour ride to Luang Prabang. We teachers are proud. The kids have worked hard recording painful interviews relaying the tragic realities of peasant life in this remote province of northern Laos. Xieng Khuang, the once-strategic theater of Cold War proxy-fights between communist and western forces, is now struggling to minimize poverty and maintain basic infrastructure. Some civic progress is evident from our 2012 educational adventure one year prior. The main roads in town are paved, though the dust has abated not at all. Chinese companies are bankrolling gold-extraction survey projects; Laos officials are confident these ventures will increase prosperity, though for whom remains unclear.

|

| Cave-combing for old treasures |

Along the mountainous drive, we stop and explore caves once-occupied by the Pathet-Lao, the communist resistance fighters — and sympathizers to the Vietcong– of the Vietnam-war era. The caves are remote and absent of tourist presence save our enthusiastic echoes. Students explore the caverns within, discovering graffiti dated to 1968, old relics — antibiotic medicine bottles, fragments of communications equipment and weapons — which seem to have sustained dozens of people in this secluded safe-haven. The tenacity of a besieged people speaks to us, a life of principled deprivation and struggle imagined within these dark walls. It’s not hard to speculate why a distantly superior and frustrated military power would resort to carpet bombing as the “answer” to the problem of an elusive enemy.

|

| Captivated children mimic our sign-language for “I love you!” |

40 years on, our UXO survivor interviews reveal much about the gentle Laotian spirit, their approach to misfortune, the immediate need for victim assistance, and the evident obstacles to bomb-free living. Our students ask questions designed to elicit responses that support their chosen investigative theme. Koji and Hana are exploring the concept of UXO removal: the scope and consequence of what is and isn’t being done to clear the land. Who are the key players of organizational support and in what ways can people get involved to help? Max and Shingo are cataloging the Lao resourcefulness of repurposing

|

old weapons’ materials into objects of utility. Jewelry, fences, building materials, agricultural tools and domestic items are refashioned from U.S steel bomb casings in a most haunting illustration of turning “swords into ploughshares.” Sarah and Marcy are highlighting the effect of UXO problem on children and the relationships within families over time. Gabi and Saavan are using a clinical framework of the seven stages of grief to inspire teen activism on key issues. They aim to illustrate that if young people have the courage to experientially engage in a humanitarian crisis, move beyond the shock and denial, feel the anger and bargaining, weather the sadness and despair, experience the upwards-turn, and arrive at a place of acceptance through social justice advocacy, they will thereby make a difference for thousands around the world. Aimee and Danielle’s project uses a symbol of hope from Hiroshima, applying a theme of origami crane-folding to inspire optimism in war victims to transcend their past with future dreams. Kayla and Delilah are demonstrating how, despite the horror of the secret war, the Lao ethos of acceptance found in religion,

|

|

How easy it is for kids to mistake cluster bombs for toys

|

history and custom explains their quiet resilience to the UXO problem. They intend to broaden their scope to include this unique healing influence on U.S. veterans who have returned to Laos to quiet their own emotional demons. Milo, the 6th grade scholar amongst this high school crowd, is contrasting the lives, hopes and fears of our group to that of our Laotian friends.

In the process of our investigation, we learn a great deal about our unconscious universalizing of western values. Our vision broadens as alternative viewpoints are brought before the lens. “What are your hopes and dreams for the future?” Is a puzzling inquiry to people who live exclusively in the present moment. “What would you say to the pilot who dropped the bombs and caused your dad’s accident?” “Do you know which country is responsible for the UXO problem on your land?” These are unanswerable questions to those for whom the past is to be relinquished as one season flows into the next.

|

|

Mr. Not struggles to find words to describe his feelings

|

The Lao eschew anger as an unproductive emotion. While many of the UXO survivors exhibit significant

symptoms of PTSD, clinical depression and suicidal tendencies, the concept of seeking therapy for their “mental health” is completely foreign. “Sadness is just part of life,” ThongChanh, our once-monk-turned humanitarian tour guide (who the students affectionately call “TC”) explains to us. “We don’t have doctors for mind sickness. If you’re sad, eventually you make yourself feel better.” The notion that Mr. Not, a nearly-catatonic 14 year old cluster bomb survivor will just someday “cheer-up,” is unlikely. None of his family expects it to be so. They have resigned themselves, — and by extension, the boy himself—to acceptance that he is “forever changed” for the worst.

And yet, after 25 minutes of ground-gazing, repeatedly dead-end, three word answers to our questions (“I don’t know”) — a somewhat exasperated question posed to Mr. Not (“Why did you want to talk to us at all?”) exposed the silent scream within:

“Because I hope you will help make it better so I can live a normal life again.”

As it turns out, we are all made of the same stuff: the most universal expression of humans in need is also the most basic call to action: “Please help.”

|

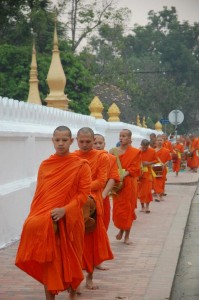

| Procession of Buddhist monks, Luang Prabang |

The gentle sweetness of the Lao people revealed again in Luang Prabang as we sit in the pre-dawn grey, preparing to feed the monks. Grace manifest, the procession of saffron-robes emerge like a quiet sunrise from the temple gates. In silence, they receive our offerings, eyes downcast in humility, disappointed at nothing.

How will the students weave the personal narratives they’ve collected into a force of good? We brainstorm the possible “calls to action” their videos will compel from sympathetic viewers. Victim assistance, educational campaigns, UXO clearance, pressure Congress to appropriate funding, sign the cluster-bomb and land-mine ban treaty. Which is most effective? What will bring the most immediate relief from this decades-long legacy of unjust suffering?

|

| Students wait to give alms of rice to the monks |

Our final debriefing session reveals a wealth of creative Possibilities: Saavan believes education is the best long-term solution. Aimee observes that while this is true, going to school is a luxury that a paraplegic-bread-winner’s family can ill-afford. Max agrees that we must be careful not to impose “our idea” of what a “better job than farming” might look like for Lao people. Hana is in support of using our existing democratic process to demand the U.S. policy-makers take immediate clean up action. Sarah reiterates the importance of preventing future UXO tragedies: shouldn’t all cluster bomb victims have priority in getting their land cleared? Delilah believes in a multi-lateral approach, including a modification of our current foreign policy. Why haven’t we signed the cluster bomb ban treaty? Danielle is passionate about designing the artistic layout for a silent auction. Gabi says that the mind responds most effectively to three choices and we should narrow our options down. Kayla suggests that all of our ideas fall into three categories of hope: “taking responsibility for the past, providing relief in the present, and preparing for the future.” Marcy agrees to write down these brilliant ideas so we can take follow-up action on an awareness and fundraising event.

Cheri Gaulke, the highly accomplished chair of Harvard-Westlake School visual arts department , and magnetic force which inspired kids to take this trip in the first place, is smiling at me. Her eyes are twinkling in that “We just created magic!” kind of way. And with full confidence in the knowledge and vision and follow-through these students now possess, I smile and twinkle, too.